Minecraft, lego made for geeks

After seeing it at the first time at Playful last month, Laura and I both picked up Minecraft, a very simple game where you explore, discover and create things in a blocky virtual world.

Minecraft is very interesting in a couple of ways. Firstly, there’s no explicit story. You’re dropped into a world with no information, no buildings, a few animals, and the sun is in the sky. It seems most ungame like, until night falls. At night, things come out, and the next day, you realise why it might be a good idea to start trying to build things so you’re safe at night. But how to build and what? Well, that’s the fun – there’s no instructions, you have to work out the mechanics of the world for yourself.

In this respect, Minecraft is almost as simple a game as you can make – a few simple rules and a little bit of motivation to apply them, and nothing else. But despite (or, I guess, because of) its simplicity, it is quite addictive. Indeed, perhaps the best testament of its powers to captivate people came in a comment from a friend, who said he knew several people had given up World of Warcraft to play Minecraft – now that’s some pulling power!

The one thing that’s struck me though, is how Minecraft is almost the perfect virtual successor to Lego. At Playful this year one of the highlight talks was by Jonathan Smith of Telltale Games, where he’s a producer on the Lego series of computer games. Jonathan himself is an ex-Lego employee, and told us that inside the Lego company the Lego system is described thus:

Infinite possibilities, systemised, with both discrete and overt affordances.

A box of Lego bricks can be put together in unimaginable ways (the infinite possibilities), but within the limitations of how the bricks fit together (systemised). The bricks themselves have an obvious way of joining together (overt affordances), but as anyone who’s played with Lego as a child can tell you, there’s other ways you can put the bricks together, like the minifigs toes can wedge between rows of studs on top of a brick (the discrete affordances). Minecraft has exactly the same properties in its game play mechanics.

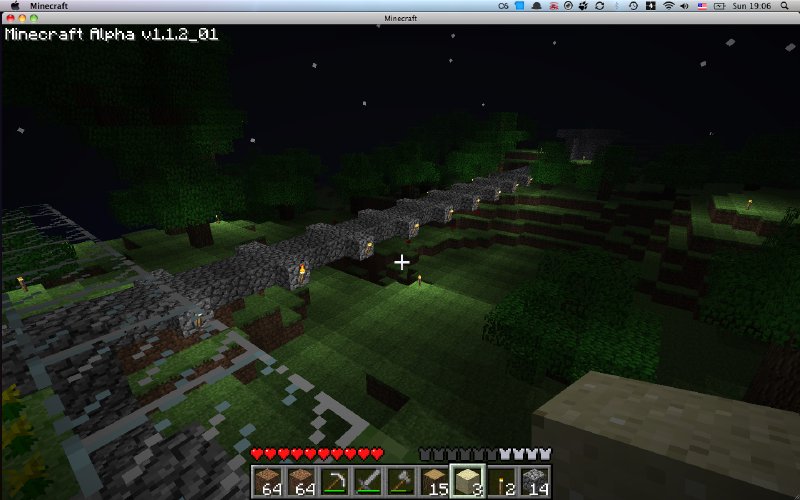

But even more like Lego, Minecraft offers this safe world in which for you to create whatever you like, either alone or with friends. Just flick through some of the images of what individuals and teams have created in Minecraft and you can see how people have seen it as more than just a simple game, but as a sandbox in which to play, creating wildly imaginative things out of a few simple building blocks. Building the bridge in the screen shot above reminded me of the kind of things I used to build when I had Lego as a child.

Another similarity can be found in how Jonathan described the key game design task for them was trading off player freedom to do anything, with what is expected from them in the world. Modern games all tend towards open worlds in which you can do things in your order, but for there to be a game, you need some sort of tasks or missions you require your used to do. Total freedom is boring, too much being told what to do is frustrating. Minecraft, even more so than the Lego games, manages to give as much freedom as possible with just the tiniest bit of requiring something of the user (surviving the night).

All this then explains to me the popularity of Minecraft, at least amongst geeks – it’s like an infinite set of Lego that rewards you for the time you spend in it, and I suspect it’s more socially acceptable (thought there’s no reason it should be) for grown ups to play a video game rather than play with a pile of plastic bricks.

- Next: Moving on to new things

- Previous: Space Invaders

- Tags: Gaming, Geek, Minecraft